On a hot summer evening in Naha’s Kume village, the drone of cicadas is punctuated by the cracks of fists against wooden boards. The synchronized pounding of feet and spirited yells echo around the neighborhood. It is here at Meibukan Hombu Dōjō, and at other karate schools throughout the islands, that Okinawa’s unique culture is preserved.

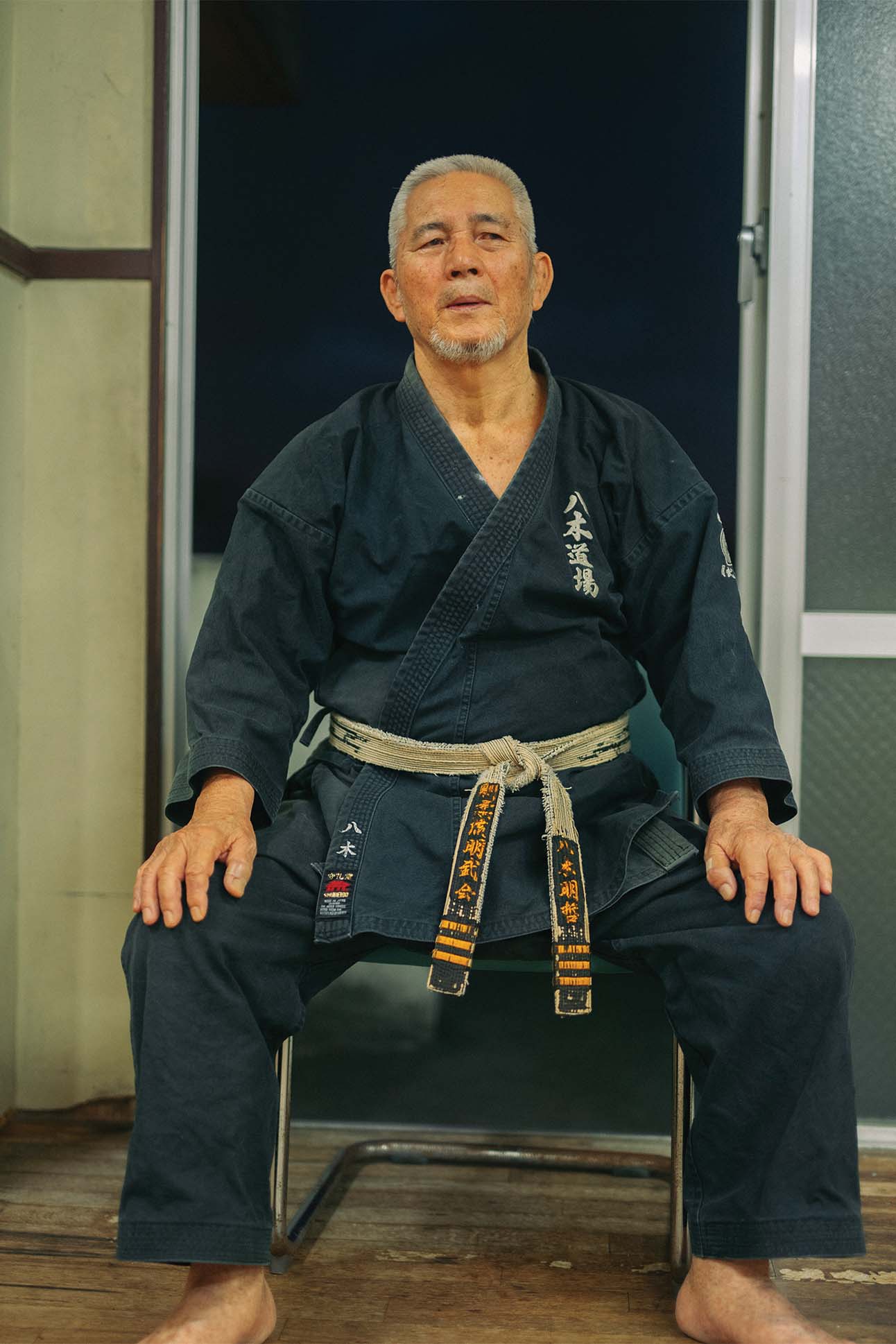

Seated in a corner is Meitetsu Yagi, a master of a style of karate known as Gōjū-ryū. He began his training from the age of 6 years old and earned his first dan (rank) in both karate and judo at age 16. Like many Okinawan karate masters, he went on to hold a day job alongside his martial arts practice, but his true passion and calling was karate. Working as a high school English teacher until he retired at age 60, he considered the two parts of his life—teaching and karate training—connected. “The goal of education and budō (the way of the warrior) is the same,” he says. “To become a nice person who can contribute to the world.”

His son, Ippei Yagi, a barrel of a man, stands at the front of the room. Gripping the wooden floor with his toes, Ippei twists his hips and powers his arm and fist into an invisible target. As an All Okinawa Karate Champion of kumite, or sparring, Ippei wasn’t known for flashy kicks or rapid strikes but powerful, well-timed blows. Today he is the next successor in line after his father to oversee many of the dōjōs affiliated with the Meibukan branch of Gōjū-ryū karate founded by his grandfather, the late Meitoku Yagi. In 1997, Meitoku became a holder of the Intangible Cultural Property title for Okinawa karate and kobudō. He is said to have learned all 12 core Gōjū-ryū kata (forms) from Miyagi Chōjun, the legendary forefather of Gōjū-ryū.

On Karate Day in 2016, nearly 4,000 participants gathered on Kokusai Street in Naha to set a new Guinness World Record for the most people performing a kata.

Meibukan Hombu Dōjō is situated in an apt location: Just a short distance away is Fukushūen, a traditional Chinese garden that celebrates Naha’s connection to its sister city of Fuzhou in China’s Fujian province, where Miyagi honed his skills. On his return to Okinawa, Miyagi blended what he had learned in China with his knowledge of Naha-te—a regional style of combat that combined Chinese martial arts and local fighting methods—to create Gōjū-ryū, meaning “hard-soft school.”

Japanese statesmen had taken an interest in Okinawan martial arts after the Ryūkyū Kingdom was annexed and became Japan’s Okinawa Prefecture, believing that their rigorous conditioning and discipline would benefit society, particularly if integrated into the education system. The term “karate,” as it came to be known, was originally written with kanji characters meaning “Chinese hand,” but in 1936, Okinawan karate masters changed its writing to mean “empty hand,” both to honor karate’s evolution beyond China and to promote its weaponless nature.

Gōjū-ryū, a distinct style of karate that combines hard, linear striking techniques with soft, circular movements, is “like yin and yang,” says Miguel Da Luz, a representative of the Okinawa Karate Information Center. “You need both aspects. When needed, you have to adjust between the two.”

It’s an attitude of non-violence, of respect toward others, That’s what karate is really about.

Miguel Da Luz, Okinawa Karate Information Center

As Ippei leads the evening’s class, guiding his young students with a tender discipline, it’s clear there is a deeper meaning to Gōjū-ryū’s duality of hard and soft. “The stronger you become, the gentler your heart should be, the more kind and humble,” Ippei says. “Karate is like a weapon. Instead of just giving students the weapon, you have to teach them the mindset. It’s dangerous to only give them the technique and not teach them the philosophy behind it.”

When he was approached by Halekulani Okinawa to offer karate lessons to hotel guests, Ippei was pleased to learn that the resort was more interested in promoting the philosophy behind the form than teaching the mechanics of combat. “The important thing is to train the body, hone the technique, and nurture the mind, [not] beat people up,” he says. “Halekulani is the only hotel that asked me to focus on the philosophy.”

As Da Luz puts it, karate is more than a martial art; it’s a way of life. “It’s an attitude of non-violence, of respect toward others,” he says. “That’s what karate is really about.”

Ryuhei Yagi, Ippei’s eldest son, stands at the center of the dojo surrounded by his peers. Moving with unwavering intensity, he performs a kata, his kiai (battle cries) piercing the thick heat of the room. Like his siblings and cousins, Ryuhei began his training at a young age, and the fruits of his labor are apparent in his fierce precision and commanding gaze. It is his spirit, however, that Ippei is most interested in strengthening. “I’m most happy when someone tells me that my students are good people,” Ippei says. “This is the philosophy at our dojo.”