Thunder rolls overhead as Nao Taira makes her way to the largest of her family’s bashō (wild plantain) fields in the northern Okinawan village of Ogimi. A shīgu—a small knife used to strip plant stalks—hangs around her neck, and her long sleeves and pant legs shield her from the giant mosquitoes hovering heavy in the air. Arriving at the edge of the field, she heads down a muddy path between walls of bashō plants, their leaves forming a canopy of green above her. A black-and-white butterfly lands on the deep purple inflorescence of a nearby bashō flower. “Obāchan (grandmother),” Nao says, spotting the insect and grinning.

When Nao made the decision to move back home to Ogimi a decade ago, it was to deepen her understanding of bashōfu weaving and of her grandmother, the Living National Treasure Toshiko Taira. Working with Toshiko in the years before her passing at age 101, Nao witnessed the fierce tenacity that enabled her grandmother to successfully revitalize bashōfu production in the village’s once-thriving Kijoka district, where the craft had nearly died out in the wake of World War II.

Even as a centenarian, when Toshiko could no longer ride her bicycle down the road, she would insist on checking on their bashō fields after the region’s frequent typhoons. “There were other people who could do it, but she wanted to see the fields with her own eyes,” says Nao, who would indulge her grandmother by taking her to patrol the fields by car. It was only in the last six months of her life that Toshiko scaled back her long hours at the workshop, though she continued to arrive before dawn to prepare the space for the day’s labor. “The mission of a Living National Treasure isn’t about resting at 90,” says Nao’s mother, Mieko Taira, who manages the bashōfu operation that Toshiko left behind upon her death in 2022. “Even after age 100, it’s about self-improvement and nurturing the next generation.”

A native of Fukui Prefecture, Mieko was familiar with her mother-in-law’s work well before she and the bashōfu artisan would go on to become family. Mieko’s interest in Ryūkyūan folk crafts brought her to Okinawa after its reversion to Japan in 1972, and by then, Toshiko was renowned for her contributions to the craft, having pursued it in earnest following a formative year of studying dyeing and weaving under Kichinosuke Tonomura, a leader in the mingei (folk art) movement, in Japan’s Kurashiki city shortly after the war.

According to Mieko, Tonomura had once commented, “‘Toshiko-san, your mind isn’t here, is it?’ When you’re lost in thought, the sound of weaving doesn’t flow smoothly—shan-shan-shan-shan. It wasn’t so much about technical teaching but about learning a kind of inner stillness.”

In a video testimony for the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, Toshiko recalled of her mentor: “Mr. Tonomura would always tell us, ‘Weaving comes from the heart, and your heart is reflected in the weave.’ He taught me not only the techniques, but also the necessary mindset for weaving.”

Returning to Okinawa from Kurashiki, Toshiko discovered many homes in her village had been destroyed during the war. The bashō plantations were gone too, burned down by the U.S. military to control the population of malaria-spreading mosquitoes. Galvanized by her new sensibilities for weaving, and by those in Kurashiki who implored her to keep the craft alive upon her return to Okinawa, Toshiko improvised. While she and her family nurtured the bashō fields back to life, they collected thread from the silkworms in their house and unraveled discarded military blankets and tents to repurpose the cotton for weaving.

“Back in the day, bashōfu was a family business,” Mieko says. “The grandfather would take care of the land, the grandmother would produce the thread, and the children would help whatever way they could.” After the war, however, with the village’s imperiled bashōfu industry offering little economic opportunity, many men began leaving to seek carpentry work in urban areas outside of Ogimi.

It was thus the women of the village who Toshiko enlisted to join her in resuming bashōfu production, forming a cooperative dedicated to the preservation of Kijoka’s weaving techniques. Together they developed intricate kasuri (ikat) patterns unique to Kijoka, as well as novel items such as table linens and cushions. The enterprise proved popular among American military families, and once again Kijoka was recognized for the beauty and value of its bashōfu culture.

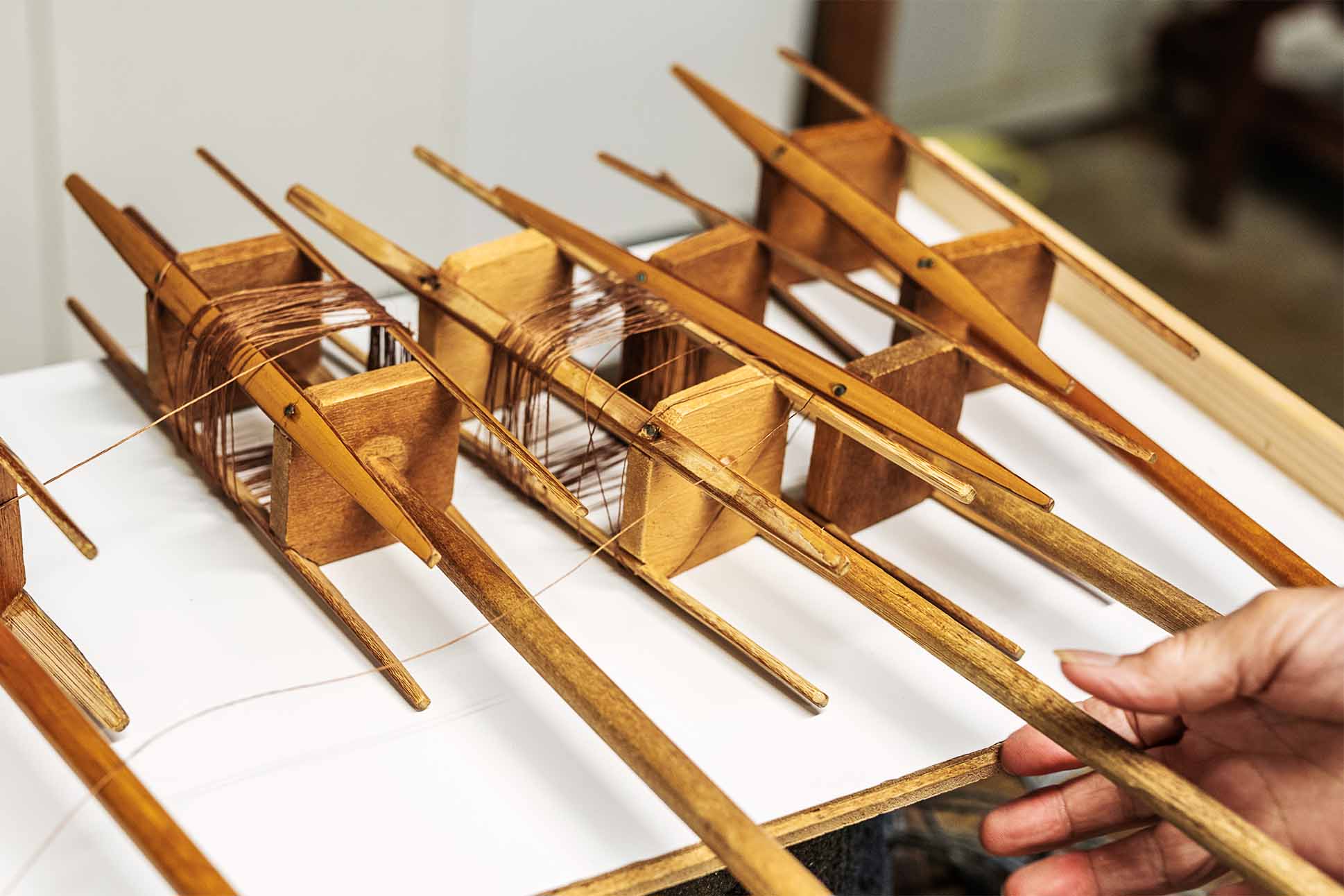

Today, like so many before it, the air in the weaving room at the Kijoka Bashofu Weaving Studio is thick with a damp heat, primed for the work ahead with humidifiers that keep the delicate bashō fibers supple and resistant to breaking. The gentle whirring of an ūchingibata (spinning wheel) and the humming of fans join the chorus of cicadas buzzing in the trees outside. In an adjacent room, another sound punctuates the quiet: that of porcelain knocking against wood as Mieko rubs an inverted chawan (teacup) along a bolt of fabric in long, firm strokes on the floor, imparting a smooth texture and sheen.

In opening the studio for tours, Toshiko intended for the public to observe the meticulous work of transforming bashō into the distinctive textile known as Kijoka bashōfu, a long and elaborate process requiring deft skill, mathematical precision, and many hands and months of manual labor. “Toward the end, her focus was ensuring that bashōfu would find its place in the world,” Mieko says, an effort Toshiko specifically geared toward curators of museums and art institutions in hopes that, through their collections, bashōfu could be shared and preserved in perpetuity.

“But the aim wasn’t to create works of art,” Mieko is quick to clarify. “It was to create fabrics that people would want to touch and wear.” With her producer’s mindset, Toshiko had a keen sense of how to bring out the essence of the material—allowing even lower quality fibers to shine—all the while facilitating better working conditions, higher production standards, and opportunities for others to learn and refine the craft. “Rather than changing the fabric itself,” Mieko says, “I believe her greater impact was in transforming the environment around it.”

With its striking patterns, rich heritage, and hard-won esteem, Nao says there’s no shortage of young people interested in the idea of weaving bashōfu. Few, however, are committed to the reality of the craft. “Good plants are key for good thread,” she says, explaining that a weaver’s work begins in the field, three years before the bashō is ready to be harvested. “There are people who come here to learn about bashōfu but can’t handle the lifestyle. They say, ‘I didn’t come here to do weed-pulling. I didn’t come here to work in the fields,’ and leave.”

This hard truth is what keeps Nao in Kijoka working alongside its aging elders, some of whom have been fixtures in her life since childhood. “If they say they want to keep making thread even when they are 80, 90, or 100 years old, I’ll stay and harvest the fibers to give them,” she says, tears welling in her eyes. “No one is commanding me, and it’s not something I feel I’m obligated to do, but every time I’m asked, I realize I have to do it.”

As if they were a part of the landscape, Nao remembers seeing the women of Kijoka out on their porches every morning on her way to school, tying bashōfu threads under the eaves. To preserve the traditions of Kijoka bashōfu is to preserve the spirit that made it the lifeblood of the village—and to uphold the values of a community that looks after each other like family. “The hearts of the people involved must come together as one,” Mieko says. “United in heart, the bashōfu bears no author’s name. It’s a collective effort.”