A heavy summer rain batters my umbrella as I wait for artist Moeco Yamazaki outside the Koishikawa Botanical Garden in Tokyo’s Bunkyō ward. We’ve decided to meet here, the oldest botanical garden in Japan and one of the oldest in the world, to discuss the journey that brought her from Tokyo’s concrete maze to the pastoral countryside of Okinawa. Despite the hidden splendor of this urban oasis, it is a pale substitute for the wilderness of Yonaguni, the remote Okinawan island where Yamazaki’s artistic practice took root and that continues to act as her muse, studio, and second home.

Yamazaki arrives wearing a knitted black dress and her hair in a long braid. We head into the botanical garden, handing our tickets to the women in the entrance booth, who inform us that we have the entire 160,000 square meters of the garden to ourselves. Benefits of a typhoon-induced downpour.

Following the asphalt path to the greenhouse, we pass banana trees and sotetsu plants, both common in rural Yonaguni, less so in the middle of the world’s biggest metropolis. We enter the greenhouse to escape the rain, and I start by asking Yamazaki if she considers herself more of a photographer or an artist.

After a long, thoughtful pause, she explains that she is no longer sure which of her chosen mediums is driving her practice, analog photography or the traditional paper she creates to print the images on. “I often feel like I am making photographs simply to have something to put on to the paper,” she says, unwinding and re-braiding her hair, now damp from the rain.

Life on Japan’s westernmost inhabited island has profoundly influenced Yamazaki’s sensibilities as a creative, prompting her to expand beyond the bounds of photography into the more tactile craft of Ryūkyūan papermaking. Yonaguni is now where she spends much of the year, keeping a studio on the island. But how did she end up basing her creative life in such a remote place to begin with?

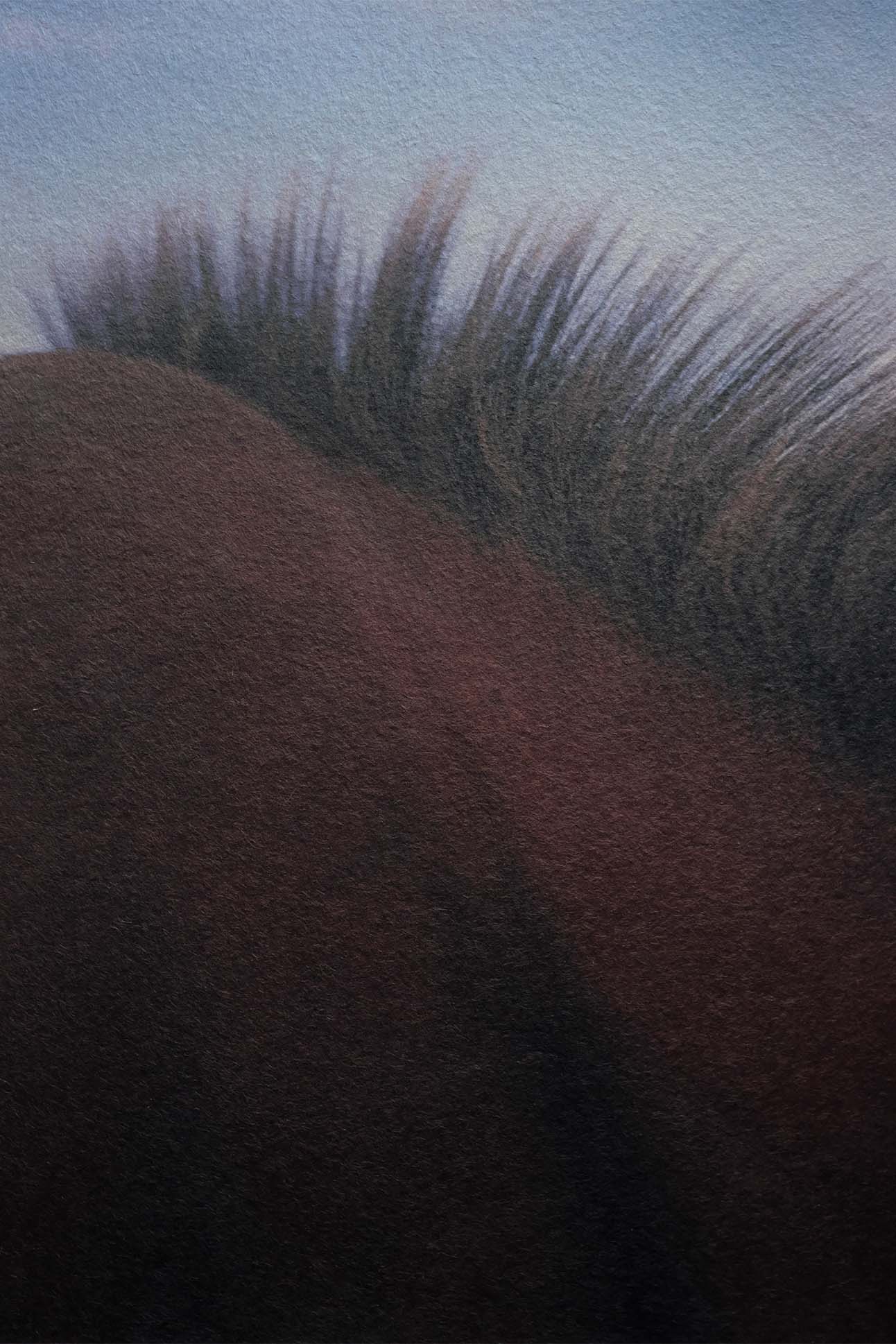

“In 2021, I wanted to see the native horses living on the island and get some traditional grass sandals,” she says. “I saw how the Yonaguni horses live and die in the wild, left to decompose naturally and return to the earth. Seeing that process of life and death play out, I thought, ‘This island is a special place for me.’ I was immediately drawn to it.”

A speck in the Pacific at just over 11 square miles, Yonaguni is part of the Yaeyama Islands that form the southern reaches of the Ryūkyū archipelago, lying closer to Taiwan than to the Okinawan capital of Naha. (It is said that on a clear day, you can see Taiwan’s mountainous silhouette on the horizon.) It wasn’t until the 15th century that Yonaguni was incorporated into the Ryūkyū Kingdom, which was then itself annexed by imperial Japan in 1879, so it is culturally a world apart, sharing influences with the native cultures of Taiwan as well as those of Okinawa and mainland Japan.

Even within the Yaeyama Islands, Yonaguni is a world unto itself. It lacks the stunning coral reefs of other islands throughout Okinawa but counters with no shortage of natural wonders, from the mysterious underwater Yonaguni Monument to the rock formations Gunkan-iwa, a stout obelisk named after a warship, and Tategami-iwa, a towering candle-shaped rock, which rise from the seafloor off its craggy southeastern coast, mirroring the two lighthouses that stand like sentinels on opposite ends of the island. “Surrounded by the nature of Yonaguni, I felt a return to my childhood senses,” Yamazaki says. “Seeing the withering body of a dead horse, touching plants and soil—these primordial experiences still bring out pure emotions, unbound from modern social concepts.”

From this state of primal curiosity, she felt compelled to create something with her hands and decided to try making traditional straw sandals from wild plants on the island. “I didn’t know anyone before I got there,” Yamazaki says. “I was told to search for Yuu Yonaha, a local Yonaguni craftsman, who taught me how to source plants and make grass sandals. I decided then that I would create some kind of art from the island’s plants.”

She says that although Yonaha wasn’t a papermaker, he taught her a posture and spirit that now permeate all aspects of her life, from papermaking to cutting and gathering grasses, even cooking meals and carrying out daily tasks. The experience induced a permanent shift in her awareness and artistic intention. “He made me expand beyond my five senses and taught me a different way to experience the world,” she says.

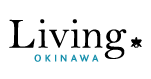

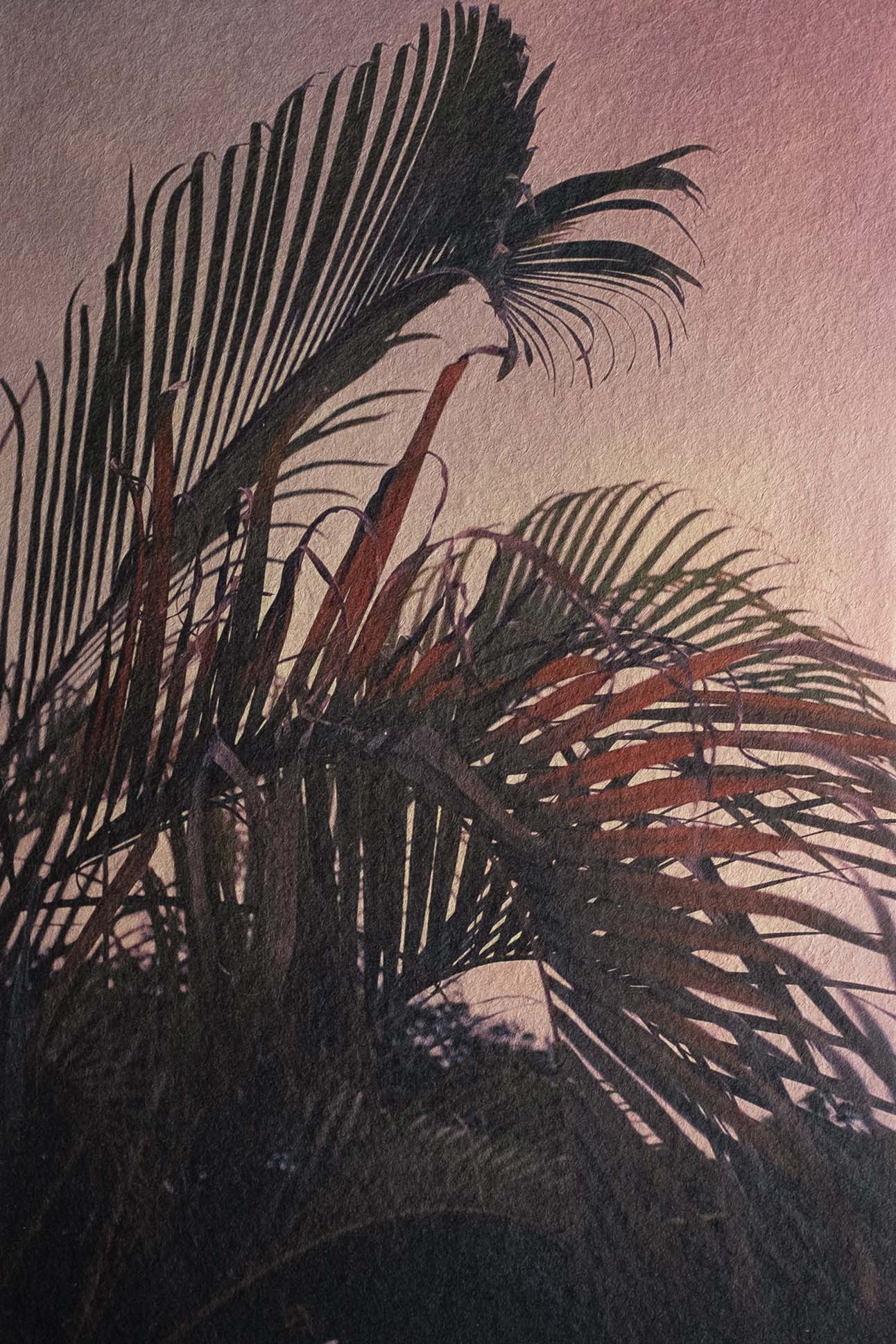

Yamazaki then consulted another craftsman on the island, and their conversations led her to the Southeast Asian practice of making paper from the dung of grazing animals. She found a Thai papermaking workshop on YouTube and experimented with making paper from the dung of Yonaguni horses, mixing it with fibers from ito-bashō (a native variety of banana plant used to make lightweight fabric) and other plants on the island. “On that paper, I printed photographs I took there, which was the beginning of my current practice,” Yamazaki says. “Using natural dyes like indigo, mud, and squid ink adds a sensory layer to the artwork, capturing the wind, scent, and spirit of the place where the photo was taken.”

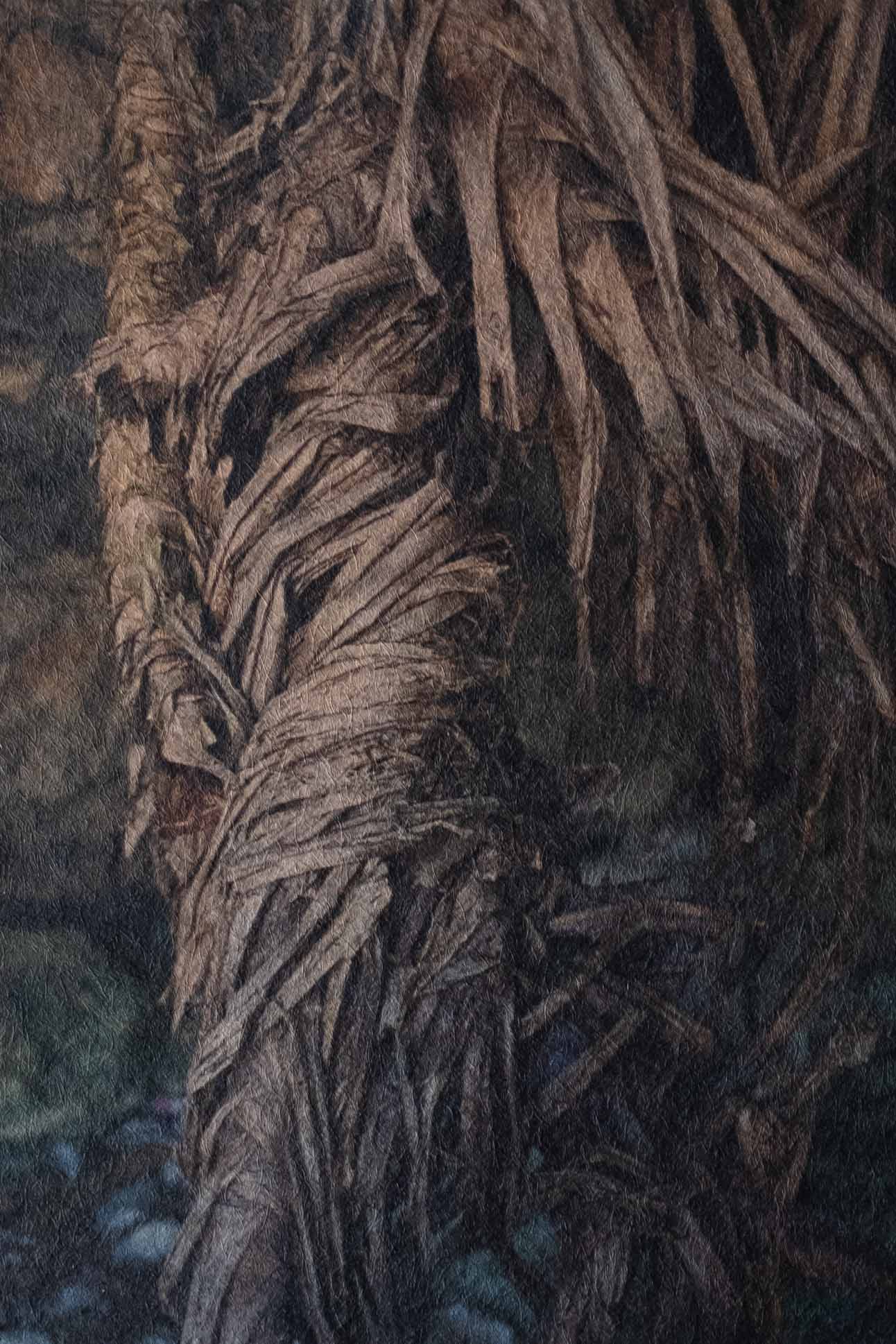

Now, she says, “When I take pictures, I’m not just capturing a scene. I aim to grasp the air, the scent, the invisible atmosphere surrounding the subject. In Japanese, the word for photography, ‘shashin,’ means ‘to reflect truth.’ But true reflection is elusive; what we see is shaped by perception.” By printing on textured paper that obscures the details of the subject, Yamazaki continues, “I revisit the original intent of photography and simultaneously blur the boundaries of reality.”

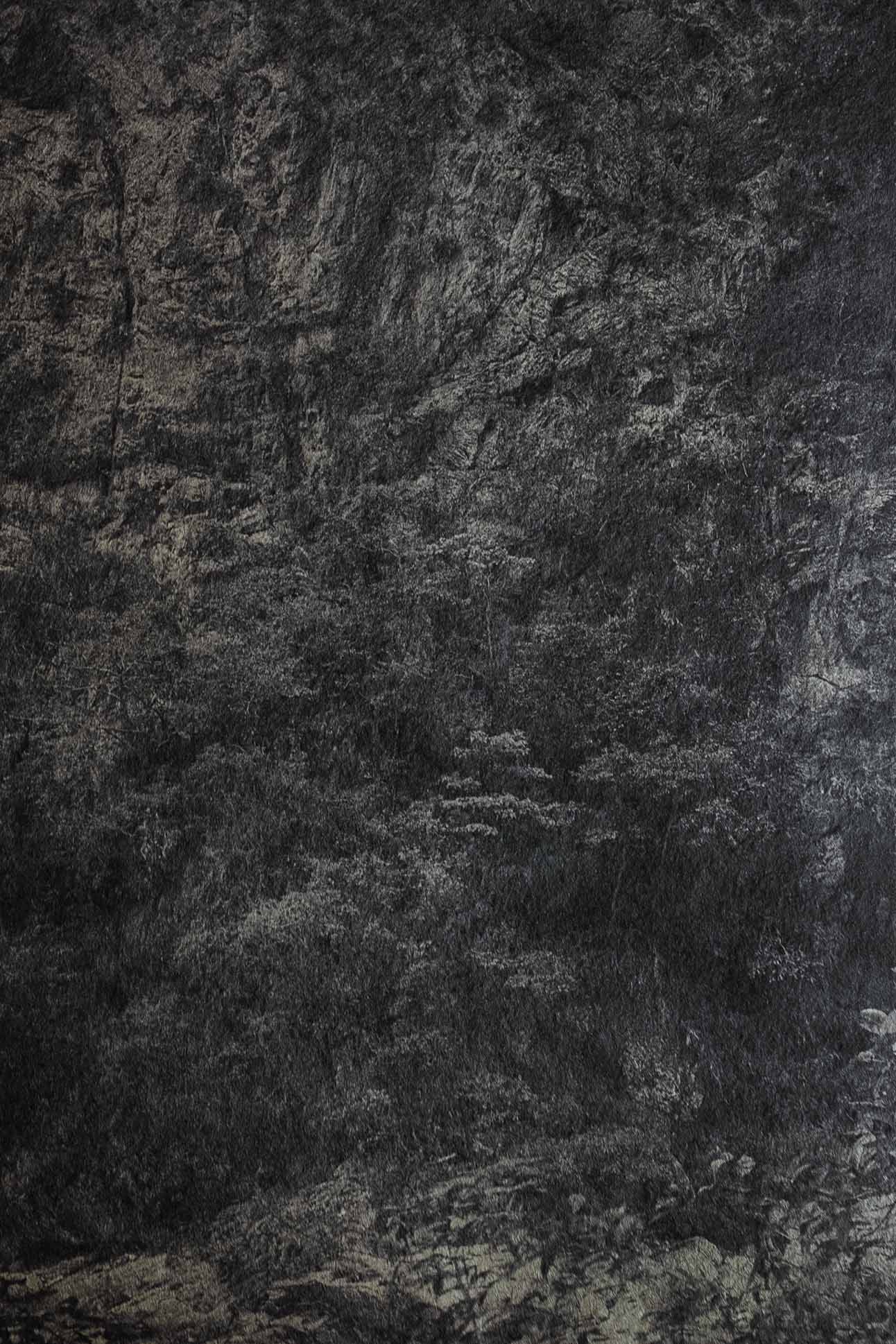

She recalls an evening during the Jūgoya full moon festival on Yonaguni when a transcendent moment of dancing barefoot in the darkness sharpened her awareness of the night around her—the sounds on the wind, the damp soil and wet grass beneath her feet. “I felt profoundly connected to the earth,” Yamazaki says. “Each sense heightened, and even my hearing became more attuned to the subtlest sounds.”

Moved by the rhythms Yonaguni has awakened in her, Yamazaki’s work has evolved to tell a deeper story of place, one rooted in the land’s ebbs and flows, in her simple daily routine, in the lives of those born and raised on the island. The resulting portraits are more subjective, perhaps, more personal and inscrutable—evoking, in the process, something truthful about the way of being she has discovered there.